Apia Harbour in February and March was, and perhaps still is, a dangerous place. Every year, the hurricane season ends with a flourish, and gales, storms, and yes, on occasion, a hurricane, ferociously attack any ship huddled in the bay, surrounded as they are by vicious coral waiting to snare anything not securely anchored to the muddy floor of the bay. In the really bad hurricane of March 1883, many ships had been destroyed, though thankfully the loss of life was low, capricious nature at that time had been kindly.

In those two months of 1889, a number of fierce gales had assaulted Apia bay and its occupants, the locals attesting that the last two had been the worst they had experienced. Whilst some smaller merchant vessels had been swamped and cast ashore or dashed against the reef, the imperious warships with their great hulls, massive anchors and heavy chains, had weathered the power of wave and wind with little trouble. Steam had been got up regularly, and used to ease the strain on the moorings, but none of the vessels had been in serious trouble. Only SMS Eber had dragged against the reef, sustaining damage to her screw which, though on the face of it minor, was in reality a serious risk should another blow come on, and her engine be needed again.

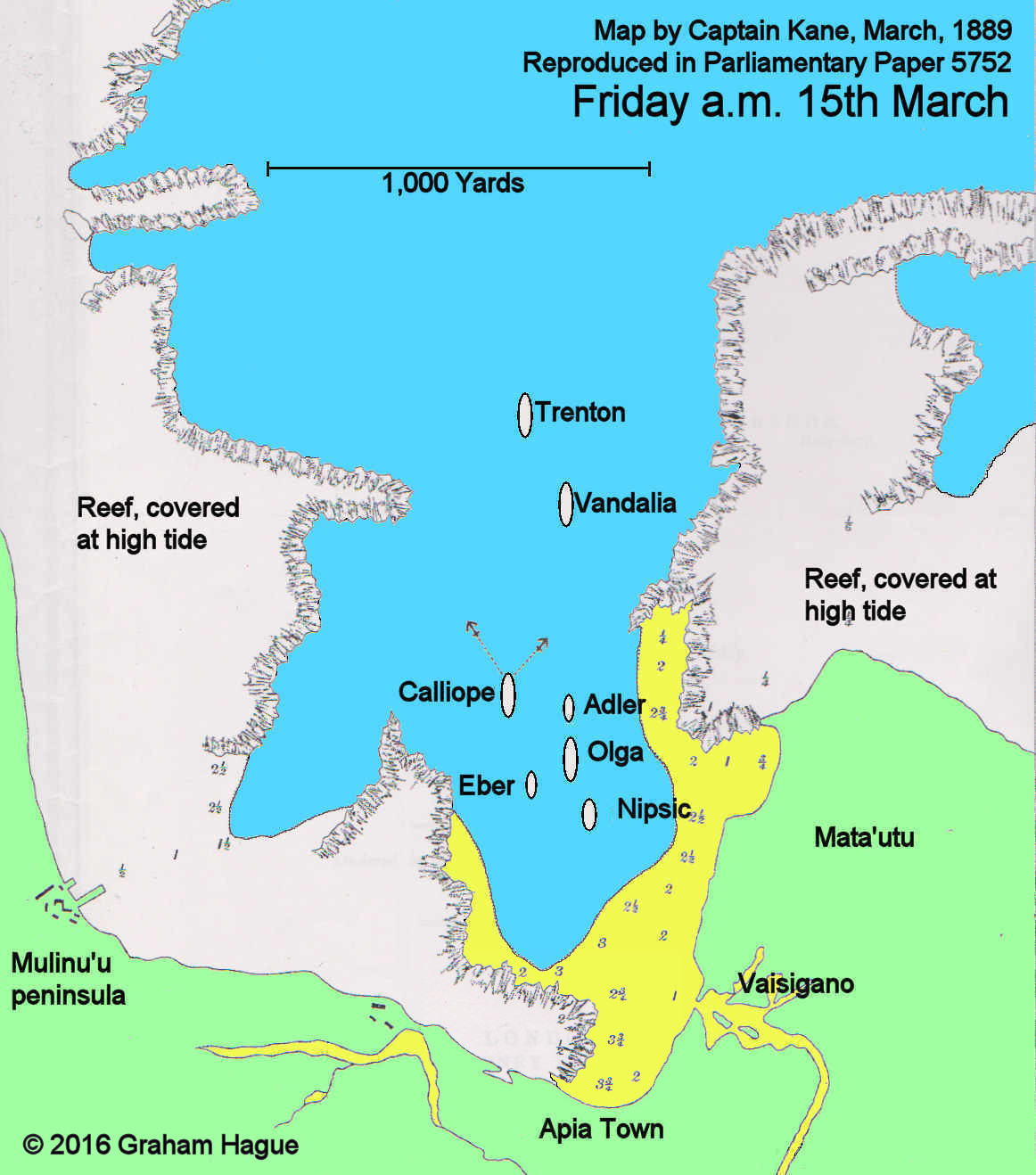

The map above is scanned from Captain Kane's map reproduced in Parliamentary Paper 5752, coloured by Scaramouche, and shows the positions of the main warships just before the hurricane started. Click the image to see it in a larger scale.

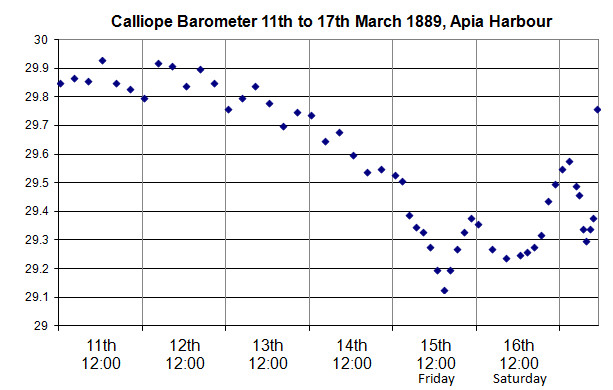

Another typical Apia storm was ending on the morning of Thursday 14th March 1889. The gales had been rough as usual, and had welcomed the bay's final guest, the massive USS Trenton in much the same way others had been welcomed. The calming seas and wind seemed to be the harbinger of the settled weather of what was (for the southern hemisphere) the coming winter. But the barometer, that universal measurement of weather conditions and predictor of the future, was acting strangely, falling steadily all day. The winds were light and the sky clear, and some wondered if the gale just past might be making a return, such things were not unknown.

The ships crammed into the bay were fitted with the latest weather devices of the time, and navigating officers experienced in how to read them. The sailors, with only experience and instinct to go on, had the ominous feeling something big was coming. The captains of all the ships, most of whom felt the same as their crews, during that day took the opportunity to go ashore and talk to the local experts: old sailors and captains who had seen Apia in all its various guises, and who knew better than anyone what the signs meant. Unusually for a parcel of experts, all were in agreement, the fall indicated heavy rain was coming, but there would be no wind. The stormy season was over, it had gone out violently, but gone it had.

On HMS Calliope, Navigating Lieutenant Henry Pearson watched his barometer and came to a different conclusion. The wind which was attested would soon be disappearing, was nevertheless rising from the south, and an offshore wind at Apia with falling pressure usually meant only one thing: hurricane. He voiced his fears to Captain Kane and recommended getting out of the cluttered bay and its encircling coral reef, but was over-ruled. The shore based advice, combined with the knowledge that those two recently weathered storms, the worst in living memory, had been easily seen out by a powerful ship with her massive holding gear properly deployed and steam in readiness, led the Irishman to dismiss those vessels lost 7 years earlier as "wind-jambers" only. To level an accusation of arrogance would be unfair to the man, as it would be to all the other military captains who accepted the same advice from local residents. These warships were not there to trade or ferry tourists, they were there to defend their national interests. The Americans had been incensed by the waving in Congress of the burned and tattered "Old Glory", and with the nation which had made that insult sitting just across the bay and dictating Apia policy to the betterment of German interests only, there was no way the United States would sail out of the harbour and leave their interests unprotected. If war was coming, and it seemed unstoppable, neither German nor American forces would leave the field to the other.

Early on the Friday, the wind had indeed dropped, but the temperature was hot and sultry even for Samoa. The waters of the bay seemed to be covered by a sheen of greasy oil. Late on the morning of that Friday, the Navigating Officers on all the ships recorded yet another drop in the barometer, and despite what may have been said ashore, preparations for a heavy blow were at last made. The evolutions on each of the warships was to "Strike Lower Yards and Top Masts", one of the heaviest to be performed. Sails were furled and lashed, and the lowermost yards which carried the majority of the sail on a ship were detached, lowered to deck and stored, lashed widthways across the deck and protruding 20 or 30 feet either side of the hulls, or sometimes stowed length-ways along a ship. The upper portion of the fore- and main-masts were detached from the cross-trees and lowered to be housed against the main part of the mast, leaving only the gallant yards for sail. By early afternoon, the ships and men were ready, but the normally busy waters of the bay were deceptively calm and still. So far, the local experts were right, there was no wind.

As the oppressively hot afternoon wore on, the skies darkened and that forecast rain came; heavy, sheeting rain, torrential in every sense of the word, screaming like bullets from suddenly livid-hued skies. Waves started to get up and the wind, that wind not supposed to be present, freshened inexorably. But still as yet, safely from the south.

The evening darkness closed early, and as it did so the wind, strengthening all the time, swung to slightly east of north. Soon the wind had outstripped those previous, safely endured, gales, and now that worst situation each captain had dared not contemplate seemed destined to hit the ships, a severe northerly gale in a tiny, crowded bay, encircled by treacherous reef, and at night. Any thoughts now of trying to leave Apia would have to wait till the light of morning. During the evening boilers were lit in each ship, and steam was got up in readiness. By midnight, it was blowing a gale - Kane would before long be describing it as a hurricane - and all ships were steaming hard in an effort to ease the strain on their anchors. The darkness was absolute, the illusionary comfort of seeing other ships - be them friend or foe - sharing the dire predicament just a few yards distant was cruelly denied the crews.

Ashore, few were asleep. Those same land-lubbers who had earlier dismissed the barometer's warning had no doubts now that the ships in their bay were in the severest peril. Many Apia residents hurried in the darkness and screaming gale to the harbour, bravely negotiating the swirling Vaisingano which was now a fearsome barrier as the driving rain swelled its normally placid flow into a vicious torrent which washed away all the bridges over it, only to find themselves impotent to help the sailors. No-one could contemplate what the morrow would bring.

The moon, only a day off full, failed to illuminate any part of the bay in which the seven warships now struggled to survive. Before the meagre dawn had even tried to appear, the German gunboat Eber, that damaged screw failing her as her Captain had feared it would, had finally succumbed and been dashed against the reef, breaking into many pieces and drowning some 73 men, only 10 surviving by some never-understood miracle to join 5 lucky crew members on shore on sentry duty. Earlier even than that, two merchant ships, one Danish (presumed to be the Santiago) and the other possibly the 660 ton German iron barque Peter Godeffroy had collided and preceded the warship to the bottom of the harbour.

That miserable dawn showed the remaining vessels in pitiable plight to the onlookers on shore, who now realised they were helpless witnesses to a disaster of awesome magnitude. The mighty warships were now barely visible from just 100 yards away, as tumultuous seas broke green over their main decks: the marching breakers hiding them deep at one moment, lifting them high the next. On Adler, Kapitan Fritze realised he would soon be following Eber to the bottom, his final remaining anchor just could not hold and earlier collisions with Olga and Nipsic had caused much damage to the hull as they had cut the other cables. So he ordered that last remaining hawser to be slipped just as a huge wave approached in the hope his vessel would be borne onto the reef instead of against it. It worked, though she was toppled to her side and 20 men lost their lives; the others huddled in the rigging and only poorly sheltered by the upturned hull, enduring agonies only to be wondered at for more than a day, before the storm subsided sufficiently for them to be brought ashore.

USS Nipsic was also losing the battle, collisions with Adler and Olga had already cost her the smokestack, and the reduced draught severely impaired her screw's efficiency; Captain Mullan threw pork fat from the ship's rations into the furnaces, slipped his anchors and somehow managed to beach on the eastern shore, one of the few places the reef was absent. In doing so, Nipsic ran down the schooner Lily at her moorings; the little ship was swamped almost immediately costing 2 crew their lives.

In the outer part of the bay, USS Vandalia was in trouble. Her anchors were slipping and some cables had broken. She could not hold against the fury of the storm and was being driven inexorably further into the bay to menace Olga and Calliope. USS Trenton, too, was struggling with the flooding on her main deck through the hawse pipes menacing her boiler room.

HMS Calliope was hemmed in by the reef behind, Olga to starboard and Vandalia ahead and to port. A number of collisions determined Kane on the only course open to him: he must try and go out.