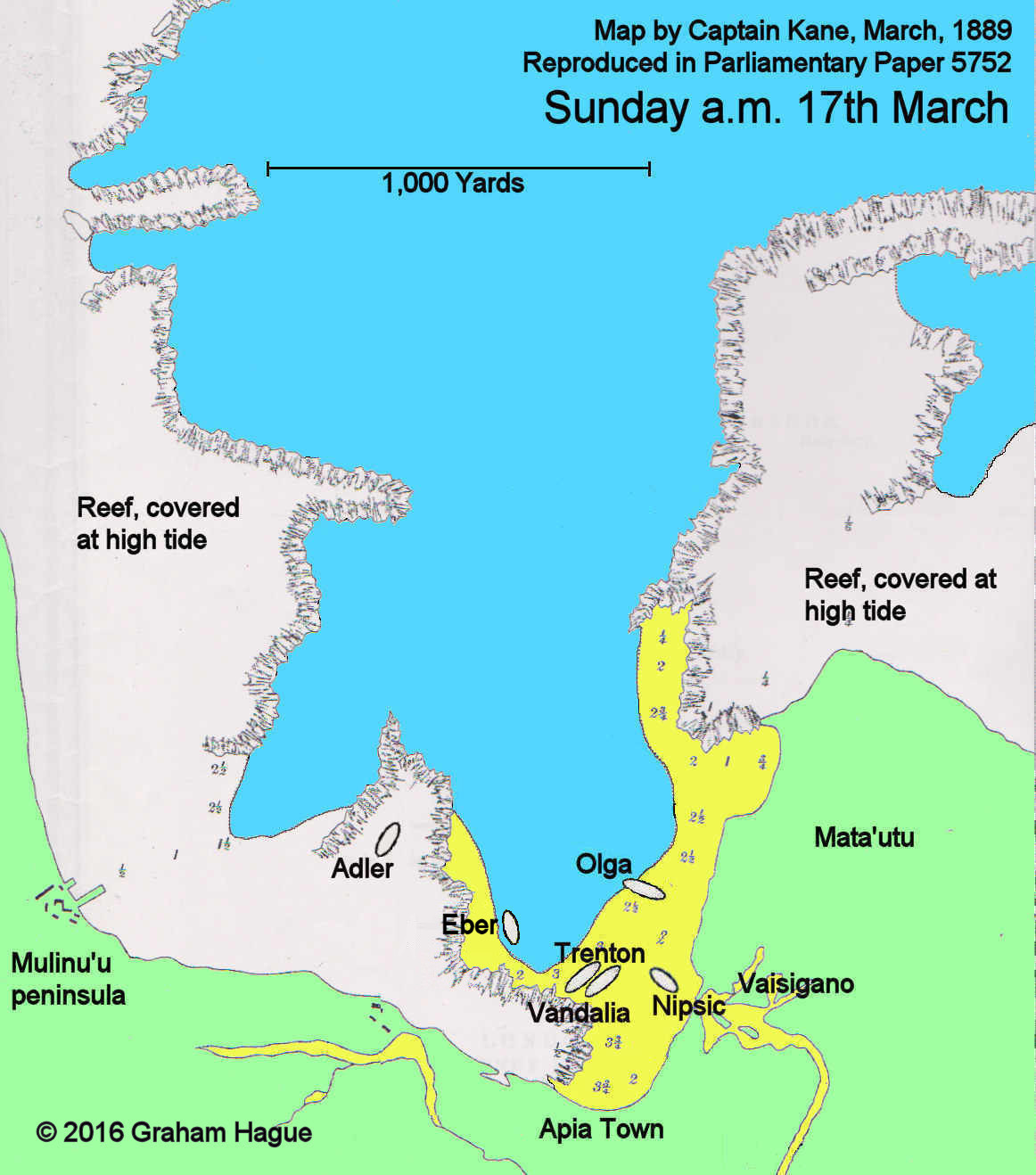

Following the miraculous escape of HMS Calliope described in the previous page, the storm if anything, gained force, such that had Captain Kane left his decision to leave any longer, it is extremely doubtful if he would have succeeded. USS Vandalia and SMS Olga endured a number of collisions, each ship suffering more and more damage, though Olga was still the most securely placed vessel. USS Trenton continued to drag further into the inner basin of the little bay. By early afternoon, these three warships were the sole remaining vessels afloat at Apia.

Vandalia's anchors finally could hold her no more, and as they parted, an unusual current caused by the vast volumes of freshwater poured by the rivers into the bay from the torrential rain on land pulled the vessel south-eastwards along the side of the western reef, behind Olga whose officers by great skill managed to avoid further collision with the rudder-less American vessel. Skirting the edge of the reef, Vandalia appeared for a moment to be approaching the relative safety of the sandy beach, but eventually her stern hit the reef and she foundered to her main deck.

Samoans, shore-based marines, traders in Apia of every nationality, all watched helplessly as one-by-one, the efforts of the crew of Vandalia to get a line ashore failed from less than 100 yards distance - it might just have been a mile. Every boat launched into the huge seas was immediately swamped and its crew dragged straight to the middle of the bay where they drowned. Finally the attempts were called off, and Captain Schoonmaker ordered his crew to the rigging as the ship settled deeper, there to await whatever would be their fate. The captain himself, exhausted and injured, was washed from the deck and drowned in full view of his men.

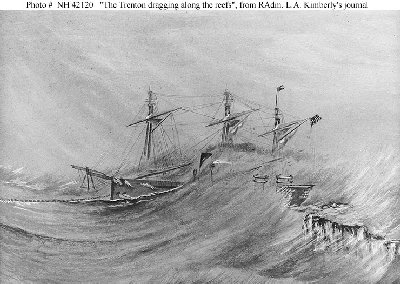

The sketch by Admiral Kimberly of USS Trenton in the storm seems to be no exaggeration. Waves regularly ran their way along the deck without breaking, so huge were they. And Trenton, like the other ships, was always close to the reef. The peril the ship is in can be clearly seen in this sketch, and all the other ships faced similar dangers.

All that now remained in the bay were the two largest vessels of the respective protagonist's fleets, powerful warships yet powerless against the relentless fury of the storm. The American flagship Trenton continued to drag, and finally her remaining cables parted. She dragged across to where Vandalia had been that morning, and menaced once again Olga. This time, the uncontrollable American vessel could not be avoided despite extremely skilful use by the German of rudder and screw, and violent collisions occurred, severing two of Olga's anchors which had hitherto withstood the force of the gale. Erhardt realised that he had come so very close to weathering the storm at his mooring, but the fates had conspired against him - two anchors would not hold him off the reef. Slipping his cables, he was somehow able to steam to the far eastern shore and, just a hundred metres or so north of Nipsic, beach the severely damaged Olga, where she withstood the rest of the storm in comparative safety - the only vessel, along with Calliope, not to lose any life.

For Trenton with no rudder and her fires out, such self-determining luxury was denied; the current took her as it had earlier taken Vandalia along the southern edge and toward the other American vessel. Almost it seemed, the forces of nature here relented for a short while; as the ships closed on each other, something kept them apart for just sufficient time for the Vandalia's crew to transfer from the rigging of their sunken vessel to the flagship. Just as the last man crossed over, the storm re-took control and smashed the vessels together, throwing Vandalia's masts just now emptied of men into the raging surf. Only one man on Trenton would lose his life. The strange current that had dragged Trenton and Vandalia along the eastern and southern reef edges turned Nipsic so that her stern pointed back out to the bay.

And so for the rest of that fateful day, men huddled on their ships and waited. On SMS Adler, the wait was in appalling conditions, the upturned hull constantly battered by enormous waves for more than 24 hours before they could be got off - some it is said, demented from the experience. On Olga by contrast, the sturdy vessel, despite taking severe damage from the earlier collisions, was fairly safe. The crew of USS Nipsic had eventually struggled to shore with the help of natives, though 7 brave men had lost their lives in the initial attempts to get the line ashore. The remaining crew of Vandalia, though missing 43 of their colleagues, spent the rest of the day and night on Trenton, forced into the rigging as waves crashed over the deck. Many injuries were caused simply by hanging on for so long.

Source: Larger versions of the pictures of the wrecks on this page can be viewed by clicking on them. All are downloaded from the American Naval History and Heritage Command, which also has a number of additional images (search for Samoa Hurricane, or on the name of the ships). The map of the wrecked ships in Apia Bay is based partly on Captain Kane's recollection of their positions, modified by Scaramouche with reference to the photographic record.

Sunday, March 17th 1889 saw the storm eventually begin to abate. Natives finally reached Adler and brought ashore her surviving crew. Trenton and Vandalia survivors made their way in boats those few yards to the shore, now littered with debris from ships and - it must be said - men, and joined the Nipsic crew. Of Eber, just pitiful smashed fragments remained. German shore marines posted themselves at Olga, still imagining possible Samoan attacks even as those same natives recovered bodies from the reef, still threatening with rifle and bayonet any natives who approached the party. The American consul made handsome reward for sailors saved, the German's offer was less valuable but this may have been due to the fact it came from that country's consul's own pocket. Often, it was refused. One Samoan native who days earlier had been preparing to defend his life from Germans, declined the offer of 3 dollars for each of his rescues, saying "...I have saved three German lives today, I make you a present of them." Most of the extraordinarily valuable flotsam and jetsam from shipwrecks of the time was returned without pilfering, when it was normally considered legitimate booty.

Kimberly sadly reviewed his Pacific fleet. Trenton and Vandalia were lost, both would be donated to the Samoan natives and broken up where they lay. At first sight, Nipsic looked to be in the same plight, but soon hopes were entertained of getting her off the sand, since it seemed her bottom was sound whilst the major damage caused from the huge battering her stern had received was confined to the sheathing on the hull, and to the rudder and propeller. Kimberly estimated she would need to be dragged back some 500 feet to re-float her, such was the power of the seas which had driven her ashore. A "jury-rig" rudder was fashioned, and sail used to eventually take her back to Hawaii with the assistance of USS Alert, though that would be months away.

Adler would never sail again, but paradoxically she would outlast most of the other ships with which she had shared this experience; the skeletal hull remained on the reef for more than 50 years, decaying slowly before the final few remaining beams were eventually covered by the New Government Building when that part of the reef was reclaimed in the 1970s. Click this link to open a web page from the Samoa Museum, which shows some artefacts recovered from most probably SMS Adler. You will need to scroll down a short way to find the section.

Eber was gone, along with her Captain Wallis who had earlier bitterly criticised his own commanding officer's decision to remain in the bay. A New Zealand diver named Keith Gordon has made dives on part of the wreck of Eber in Apia harbour, and recovered a few artefacts including utensils, food containers and uniform buttons; an interesting article is included in the Hurricane Bibliography page. The bow was the largest piece of the vessel to be washed ashore. USS Trenton is the large ship in the right middle ground, and Adler lies on the reef in the centre background. Samoan natives can be seen in the water scouring the reef for bodies to bring ashore.

SMS Olga was firmly beached, missing her bowsprit, and with some large holes in her hull, but seemingly sound in bottom. She would be the only German vessel to be refloated and repaired.

Calliope returned to the mouth of the bay. A sweep with the glass showed no sail afloat and Kane, expecting the bay to be dangerously encumbered with wrecks, had no intention of risking entry in the dusk so stood well off for the night. Next morning he entered Apia to be confronted with the desolation he had expected, but which was none the less shocking for a seaman to view. Whatever political differences existed, at times like these sailors faced a common foe together. Survival was applauded, death was mourned. The beached ships, those settled on the rocky floor, and Adler's exposed hull on the reef, were all terrible sights for sailors. Worse was the realisation that just 2 days before the bay had been crowded, yet now only Calliope swayed gently on the waves.

Kane had hoped to find his anchors, but extricating any from the floor of the bay where literally dozens were intertwined and tangled was impossible - even the mooring buoys had been washed away. He had only one small anchor, and had used most of his coal, and was in no mood to stay in the death-trap which was now Apia; should another blow come, a moderate gale would finish him off. Within all this tale of woe, a light-hearted thing perhaps: Kimberly, in his official report, notes Calliope's return with the comment: "...showing signs of having experienced heavy weather..." - a masterly understatement if ever there was one!

Kane handed over his diving outfit to Kimberly for use in salvaging what could be found on both Vandalia and Trenton and for the inspection of Nipsic's hull. In return, Kimberly gave Kane nearly all the boats he had to replace Calliope's smashed by the seas. Kane made ready, got some coal from the German supplier - who despite suddenly having few customers to buy it still saw the opportunity to charge an exhorbitant price for it - but it was slow work with no sizeable vessels available to carry the poor quality material out to the British ship, and Kane was desperate to leave hurricane latitudes altogether. Calliope had suffered badly in collisions with Olga and Vandalia and was in need of urgent dockyard repair herself. Soon, he would wait no longer, but left for Australia, carrying a German officer to report to the consulate and make arrangements for getting the survivors home, and after an uneventful voyage under greatly reduced sail, she arrived at Sydney on April 4th to a tumultuous welcome. An American Officer had left Apia the day before Calliope in a small schooner to intercept the mail boat.

Two days out from Sydney, Calliope had been sighted by a fast yacht which wasted no time bringing the news to the Australians, and they set about preparing the sort of reception one sees today for round-the-world yachtsmen and the like. The Governor, Lord Carrington, immediately declared that the day of Calliope's arrival would be a public holiday, and the entire townsfolk joined in the spirit, decking the town out in bunting. Bands played the popular songs and airs of the time - Rule Britannia featured heavily - and street parties were held. The passage into the harbour was fraught as Kane was surrounded by a myriad of welcoming boats, from large yachts to small rowing boats; all their multi-national crews cheering the vessel as she made her way to the roads, trying to make their voices heard over the constant braying of steam whistles. The Governor was the first dignitary to set foot on the ship, and made an impassioned speech of welcome. Early reports from the mail boat had been that all ships - including Calliope - had been lost; the ship was well favoured in the city and that early news had caused great distress, so the subsequent reports of her miraculous survival were especially welcome. Eventually, the German officer Lieutenant sur Zee Emsmann, left the ship to make his arrangements and to commission a fine claret jug in appreciation (which resides today in the family of Calliope's Staff Engineer Bourke), and Calliope was quiet again. Now, the men had the chance to go ashore, meet friends and relatives, and make their own personal celebrations.

A week or two later, Olga staggered into the roads, and spent a number of weeks - and a considerable sum of the German legation's funds - being made seaworthy enough for the journey home. By then, Calliope had been repaired and was back on active service.